Setting up ZFS as a cluster NFS

As a continuation of my series on setting up our cluster, I’d like to describe

our NFS. Inspired by UCLA’s lnxsrv NFS, which allows users to log in to any

of the many lnxsrv computers while still having access to the same files, I

decided to use an NFS. Additionally, since I had heard online that ZFS was a

great way to setup a NAS device, and after some quick Googling I found that

ZFS had native first-class support for the NFS protocol, I decided to give it a

shot. In fact, this was a significant justification for why sullivan runs

FreeBSD, as Linux doesn’t include native kernel support for ZFS.1

Some early precautions about ZFS

Before I start espousing how great ZFS has been, I think it’s worth noting that it may be far from perfect for many use cases. Had I been a little more dilligent in my Googling, I would’ve quickly discovered the one major issue in ZFS’ design that was the source of some headaches when analyzing performance. Namely, ZFS is cache-based, and does NOT support tiered storage. This is not a oversight, but rather an intentional choice in ZFS’ design, which, nevertheless, resulted in behavior which I found unexpected: a mixed pool of spinning and solid state drives may not be utilized in the most effective manor by ZFS. This will be discussed in greater detail later, but I found this behavior confusing enough to warrant placing a disclaimer at the beginning.

Our ZFS configuration

In order to create a filesystem using ZFS, you must first create a ZFS pool.

Just like block devices have partitions, which individually contain filesystems,

ZFS pools contain datasets, which (typically) house filesystems. Similar to LVM,

ZFS pools consist of vdevs, or virtual devices, which actually store the data.

For the sake of simplicity, we setup one master ZFS pool built from all of our

devices. Because we have the most storage on spinning drives, the pool is formed

of these spinning drives. ZFS has built-in support for software RAID, which we

should be using.2 Onto this pool, we create our datasets, namely /home,

which we will setup as an NFS mounted on each of our other servers. However, if

we were to mount the filesystem just like this, it would be quite slow, limited

by the read and write speed of the spinning rust. Fortunately, the folks that

wrote ZFS thought of this, and implemented an Adaptive Replacement Cache (ARC)

in RAM to allievate some of the read speed concerns. However, since we had plenty

of extra SSDs to use, we setup L2ARC (ie. Level 2 ARC) on one of them, which

expands the cache to our SSDs as well. This allievates some of our read-speed

concerns, although we will discuss some of the issues with this design later.

Once we mount our dataset as an NFS device, everything seems to be working great,

until we try a git checkout! While we’ve fixed some of our read-speed issues,

writing to our filesystem is still limited by the speed of the spinning drives.

ZFS, for the sake of preserving data integretity upon unexpected power loss,

will not buffer writes in RAM, as they would be lost in such an event. However,

ZFS does allocating a non-volatile device as a “log” to buffer writes. This log

is known by different names, depending on if the writes are synchronous or

asynchronous, but given that our NFS configuration is asynchronous, it is called

the “ZFS Intent Log” or ZIL. Here, we use another SSD as our log device.3

With all these optimizations in place, our NFS setup is pretty fast (It helps

that we also have 10Gbit networking in place)! But some aspects are stil slow:

namely, downloading a large dataset to disk is fast, but immediately accessing

it can be quite slow, as it hasn’t yet been promoted into ARC or L2ARC. This

can be quite frustrating, especially for large files where quick access is

desired, and appears to be a fundamental issue with ZFS’ focus on caching

rather than tiering. Our solution is essentially a form of manual tiering,

where on each of our GPU servers, we create a /scratch folder on a local

SSD, which allows us to guarantee fast read and write speeds, but sacrificing

coherency between each machine.

Another tool in the toolbox of setting up ZFS that I haven’t mentioned yet is

the special device. Part of the reason our git checkout example was slow

was also because checkout is bounded not only by write speed, but also by

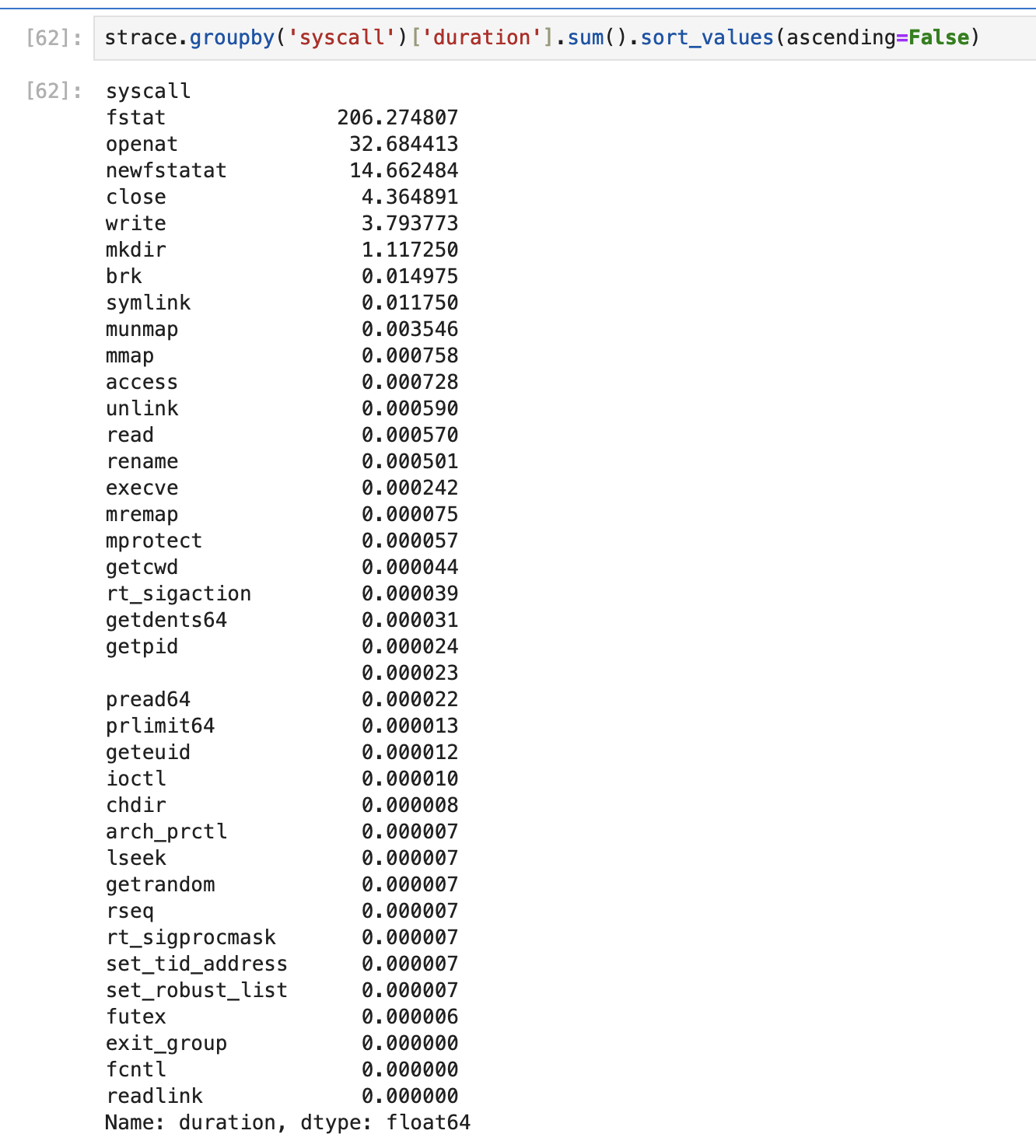

the fstat(2) syscall. Below is a screenshot showing data from

strace -T git checkout master on torvalds/linux:

As you can see, this is dominated by fstat(2). Using a special device could

fix this, as the special device, by default, will store all of the metadata

for your datasets, thus speeding up fstat(2) dramatically. The special device

can also be extended to store files smaller than a specified size, which may

result in performance improvements for various benchmarks.4

Closing thoughts

Despite the small gripes about ZFS listed above, I still think it’s a great choice for this task. ZFS excels by being simultaneously easy to use and also incredibly configurable, a rare feat. I was especially impressed by how simple the NFS setup was, a process that I did not detail here, but exists in many guides online. While I may consider switching to a tiered storage solution, for now, it seems that ZFS fits our needs.

-

I also just wanted to check out one of the BSDs, and let me say, it’s been great so far! ↩

-

Don’t follow our practices here, redundancy is great and off-site backups even better! ↩

-

Using NAND flash as a log device is not a great idea, as the constant writing and re-writing will wear down the NAND cells. Instead, using something like Intel’s Optane drives would be preferable. ↩

-

This would also be a good opportunity to use an Optane device, thanks to Optane’s low latency. ↩